When Has Islam Become Present in Turkey Again Economic Clip Art

Islam is the about skilful organized religion in Turkey. The established presence of Islam in the region that now constitutes modern Turkey dates back to the later on half of the 11th century, when the Seljuks started expanding into eastern Anatolia.[half-dozen]

According to the government, 99%[2] of the Turkish population is Muslim[vii] [viii] (although some surveys requite a slightly lower estimate of 96.2%)[nine] with the almost popular school of idea (madhab) beingness the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam. While there are also a minority of Sufi and non-denominational Muslims.[10] [xi]

According to religiosity poll conducted in Turkey in 2019 by OPTİMAR, 89.v% of the population identifies as Muslim, four.v% believed in God only did not vest to an organized religion, 2.vii% were agnostic, 1.vii% were atheist, and one.seven% did non answer.[12] [13]

Almost Muslims in Turkey are Sunni Muslims, forming near 90% of the overall Muslim denominations. The remaining Muslim sects forming about 9%[1] of the overall Muslim population consist of Alevis, Ja'faris (representing one%[fourteen] [ten]) and Alawites (with an estimated population of around 1 million) which is virtually i% of the overall Muslim population in Turkey.[xv] [16] Turkey is the 6th country with the almost muslims with 74.423.725.

History [edit]

Islamic empires [edit]

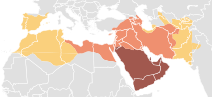

Islamic conquest extended to Anatolia during later on Abbasid menses.

During the Muslim conquests of the seventh and early on 8th centuries, Arab armies established the Islamic Empire. The Islamic Golden Age was soon inaugurated by the heart of the eighth century past the ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate and the transfer of the capital from Damascus to Baghdad.[17]

The later catamenia saw initial expansion and the capture of Crete (840). The Abbasids soon shifted their attention towards the East. During the afterward fragmentation of the Abbasid rule and the rise of their Shiite rivals the Fatimids and Buyids, a resurgent Byzantium recaptured Crete and Cilicia in 961, Cyprus in 965, and pushed into the Levant by 975. The Byzantines successfully contested with the Fatimids for influence in the region until the arrival of the Seljuk Turks who get-go allied with the Abbasids and then ruled as the de facto rulers.

In 1068 Alp Arslan and allied Turkoman tribes recaptured many Abbasid lands and even invaded Byzantine regions, pushing farther into eastern and central Anatolia after a major victory at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. The disintegration of the Seljuk dynasty resulted in the rise of subsequent, smaller, rival Turkic kingdoms such every bit the Danishmends, the Sultanate of Rum, and various Atabegs who contested the control of the region during the Crusades and incrementally expanded across Anatolia until the rising of the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman Caliphate [edit]

Start in the twelfth century, new waves of Turkic migrants many of whom belonged to Sufi orders, some of which later incorporated heterodox beliefs. I Sufi guild that appealed to Turks on Anatolia afterwards 1300 was the Safaviyya, an order that was originally Sunni and non-political but subsequently became both Shi'a and political based in northwest Iran. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Safavid and similar orders such every bit the Bektaşi became rivals of the Ottomans—who were orthodox Sunni Muslims—for political command of eastern Anatolia. Although the Bektaşi social club became accepted as a sect of orthodox Sunni Muslims, they did not carelessness their heterodox beliefs. In contrast, the Safavids eventually conquered Iran, shed their heterodox religious beliefs, and became proponents of orthodox Twelver Shi'a Islam. The conquest of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (modernistic day Istanbul) in 1453 enabled the Ottomans to consolidate their empire in Anatolia and Thrace. The Ottomans after revived the championship of caliph during the reign of Sultan Selim. Despite the absence of a formal institutional structure, Sunni religious functionaries played an important political role. Justice was dispensed by religious courts; in theory, the codified arrangement of şeriat regulated all aspects of life, at least for the Muslim subjects of the empire. The caput of the judiciary ranked direct below the sultan and was second in ability only to the grand vizier. Early on in the Ottoman period, the function of thou mufti of Istanbul evolved into that of Şeyhülislam (shaykh, or "leader of Islam"), which had ultimate jurisdiction over all the courts in the empire and consequently exercised authority over the interpretation and application of şeriat. Legal opinions pronounced by the Şeyhülislam were considered definitive interpretations.

Secularization era [edit]

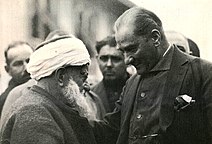

The secularization of Turkey started in the gild during the terminal years of the Ottoman Empire and it was the most prominent and most controversial feature of Atatürk'south reforms. Nether his leadership, the caliphate—the supreme pol-religious part of Sunni Islam, and symbol of the sultan'due south claim to world leadership of all Muslims—was abolished. The secular power of the religious authorities and functionaries was reduced and eventually eliminated. The religious foundations were nationalized, and religious instruction was restricted and for a fourth dimension prohibited. The influential and popular mystical orders of the dervish brotherhoods (Tariqa) besides were suppressed.

Sancaklar Mosque is a contemporary mosque in Istanbul, Turkey.

Commonwealth period: 1923–present [edit]

The withdrawal of Turkey, heir to the Ottoman Empire, equally the presumptive leader of the world Muslim community was symbolic of the modify in the regime's relationship to Islam. Indeed, secularism (or laiklik) became one of the "Kemalist credo" of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's anti-clerical program for remaking Turkey. Whereas Islam had formed the identity of Muslims within the Ottoman Empire, secularism was seen as molding the new Turkish nation and its citizens.

Atatürk'south Reforms [edit]

In 1922 the new nationalist regime abolished the Ottoman sultanate, and in 1924 it abolished the caliphate, the religious office that Ottoman sultans had held for four centuries. Thus, for the first time in Islamic history, no ruler claimed spiritual leadership of Islam.

Atatürk and his associates not but abolished sure religious practices and institutions just also questioned the value of religion, preferring to identify their trust in science. They regarded organized faith as an anachronism and contrasted information technology unfavorably with "civilization", which to them meant a rationalist, secular culture. Establishment of secularism in Turkey was not, as it had been in the Westward, a gradual process of separation of church building and state. In the Ottoman Empire, all spheres of life, at least theoretically, had been field of study to traditional religious constabulary, and Sunni religious organizations had been function of the land construction. However, commonly country had authorisation over the clergy and religious police, even at the Ottoman period (due east.chiliad.many Sultans are known to modify Şeyhülislams, who do not approve land politics). When the reformers of the early 1920s opted for a secular land, they removed religion from the sphere of public policy and restricted it exclusively to that of personal morals, behavior, and faith. Although individual observance of religious rituals could go on, religion and religious system were excluded from public life.

The policies directly affecting faith were numerous and sweeping. In addition to the abolition of the caliphate, new laws mandated abolition of the office of Şeyhülislam; abolition of the religious hierarchy; the closing and confiscation of Sufi lodges, meeting places, and monasteries and the outlawing of their rituals and meetings; institution of authorities command over the vakıfs, which had been inalienable under Sharia; replacement of sharia with adapted European legal codes; the endmost of religious schools; abandonment of the Islamic calendar in favor of the Gregorian calendar used in the West; restrictions on public attire that had religious associations, with the fez outlawed for men and the veil discouraged for women; and the outlawing of the traditional garb of local religious leaders.

Atatürk and his colleagues likewise attempted to Turkify Islam through official encouragement of such practices as using Turkish rather than Arabic at devotions, substituting the Turkish give-and-take Tanrı for the Standard arabic word Allah, and introducing Turkish for the daily calls to prayer. These changes in devotional practices deeply disturbed many Muslims and caused widespread resentment, which led in 1950 to a return to the Arabic version of the call to prayer, after the opposition party DP won the elections. Of longer-lasting issue were the regime's measures prohibiting religious didactics, restricting the building of new mosques, and transferring existing mosques to secular purposes. Most notably, the Hagia Sophia (Justinian'southward sixth-century Christian basilica, which had been converted into a mosque by Mehmet II) was made a museum in 1935. The effect of these changes was to make religion, or more correctly Islam, subject to the command of the state. Muftis and imams (prayer leaders) were appointed past the government, and religious instruction was taken over past the Ministry of National Education. As a upshot of these policies, the Turkish Democracy was judged negatively by some sections of the Muslim world.

The expectation of the secular ruling elite that the policies of the 1920s and 1930s would diminish the role of religion in public life did not materialize. Equally early as 1925, religious grievances were one of the principal causes of the Şeyh Sait rebellion, an insurgence in southeastern Turkey that may have claimed as many as thirty,000 lives earlier being suppressed.

Although Turkey was secularized at the official level, religion remained a strong force. After 1950 some political leaders tried to benefit from popular attachment to religion by espousing support for programs and policies that appealed to the religiously inclined. Such efforts were opposed past most of the state elite, who believed that secularism was an essential principle of Kemalist Ideology. This disinclination to appreciate religious values and beliefs gradually led to a polarization of social club. The polarization became especially evident in the 1980s every bit a new generation of educated but religiously motivated local leaders emerged to challenge the dominance of the secularized political elite. These new leaders have been assertively proud of Turkey's Islamic heritage and generally have been successful at adapting familiar religious idioms to draw dissatisfaction with diverse government policies. Past their own example of piety, prayer, and political activism, they accept helped to spark a revival of Islamic observance in Turkey. By 1994 slogans promising that a return to Islam would cure economical ills and solve the bug of bureaucratic inefficiencies had enough general appeal to enable avowed religious candidates to win mayoral elections in Istanbul and Ankara, the country'due south ii largest cities.

Multiparty Period [edit]

Following the relaxation of authoritarian political controls in 1946, large numbers of people began to call openly for a return to traditional religious practice. During the 1950s, even certain political leaders institute it expedient to join religious leaders in advocating more state respect for faith.[19]

A more directly manifestation of the growing reaction against secularism was the revival of the Sufi brotherhoods. Not but did suppressed Sufi orders such as the Kadiri, Mevlevi, Nakşibendi, Khālidiyyā and Al-Ṭarīqah al-Tijāniyyah reemerge, but new movements were formed, including the Nur Cemaati, Gülen move, Sülaymānīyyā, Customs of İskenderpaşa and İsmailağa. The Tijāni became specially militant in confronting the state. For example, Tijāni damaged monuments to Atatürk to symbolize their opposition to his policy of secularization. This was however a very isolated incident and but involved ane particular Sheikh of the order. Throughout the 1950s, at that place were numerous trials of Ticani and other Sufi leaders for antistate activities. Simultaneously, still, some movements, notably the Süleymancı and Nurcular, cooperated with those politicians perceived as supportive of pro-Islamic policies. The Nurcular eventually advocated support for Turkey's multiparty political organisation, and i of its offshoots, the Gülen motion, had supported the True Path Party while the Işıkçılar and Enver Ören had openly supported the Motherland Party since the mid-1980s.

The demand for restoration of religious education in public schools began in the belatedly 1940s. The authorities initially responded by authorizing religious educational activity in state schools for those students whose parents requested it. Under Democrat Party rule during the 1950s, religious pedagogy was made compulsory in secondary schools unless parents made a specific request to have their children excused. Religious teaching was made compulsory for all primary and secondary school children in 1982.

Inevitably, the reintroduction of organized religion into the school curriculum raised the question of religious college educational activity. The secular elites, who tended to distrust traditional religious leaders, believed that Islam could be "reformed" if time to come leaders were trained in state-controlled seminaries. To further this goal, the government in 1949 established a faculty of divinity at Ankara University to train teachers of Islam and imams. In 1951 the Democrat Party authorities gear up special secondary schools (İmam Hatip schools) for the training of imams and preachers. Initially, the imam hatip schools grew very slowly, just their numbers expanded rapidly to more 250 during the 1970s, when the pro-Islam National Salvation Party participated in coalition governments. Following the 1980 coup, the military, although secular in orientation, viewed faith as an constructive means to counter socialist ideas and thus authorized the construction of ninety more İmam Hatip loftier schools.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Islam experienced a kind of political rehabilitation because right-of-centre secular leaders perceived religion as a potential bulwark in their ideological struggle with left-of-center secular leaders. A pocket-sized advancement group that became extremely influential was the Hearth of Intellectuals (Aydınlar Ocağı), an organization that maintains that truthful Turkish culture is a synthesis of the Turks' pre-Islamic traditions and Islam. According to the Hearth, Islam non but constitutes an essential aspect of Turkish civilization merely is a forcefulness that tin can exist regulated by the land to help socialize the people to be obedient citizens acquiescent to the overall secular club. Afterward the 1980 armed services coup, many of the Hearth's proposals for restructuring schools, colleges, and country broadcasting were adopted. The effect was a purge from these state institutions of more than 2,000 intellectuals perceived equally espousing leftist ideas incompatible with the Hearth's vision of Turkey'southward national civilization.

The country's more tolerant attitude toward Islam encouraged the proliferation of individual religious activities, including the construction of new mosques and Qur'an schools in the cities, the establishment of Islamic centers for research on and conferences nigh Islam and its role in Turkey, and the establishment of religiously oriented professional person and women's journals. The printing of newspapers, the publication of religious books, and the growth of innumerable religious projects ranging from wellness centers, kid-care facilities, and youth hostels to financial institutions and consumer cooperatives flourished. When the government legalized private broadcasting after 1990, several Islamic radio stations were organized. In the summer of 1994, the first Islamic idiot box station, Kanal 7, began broadcasting, starting time in Istanbul and subsequently in Ankara.

Although the tarikah (the term can sometimes be used to refer to whatever 'group or sect' some of whom may non even exist Muslim) have played a seminal role in Turkey'due south religious revival and in the mid-1990s still published several of the country's most widely circulated religious journals and newspapers, a new phenomenon, İslamcı Aydın (the Islamist intellectual) unaffiliated with the traditional Sufi orders, emerged during the 1980s. Prolific and pop writers such as Ali Bulaç, Rasim Özdenören, and İsmet Özel have fatigued upon their knowledge of Western philosophy, Marxist sociology, and radical Islamist political theory to abet a modern Islamic perspective that does not hesitate to criticize genuine societal ills while simultaneously remaining faithful to the ethical values and spiritual dimensions of religion. Islamist intellectuals are harshly critical of Turkey's secular intellectuals, whom they fault for trying to do in Turkey what Western intellectuals did in Europe: substitute worldly materialism, in its capitalist or socialist version, for religious values.

On xv July 2016, a putsch was attempted in Turkey against state institutions by a faction within the Turkish Armed Forces with connections to the Gülen movement, citing an erosion in secularism.

Status of religious liberty [edit]

The Constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the Government generally respects this right in practice; however, the Government imposes some restrictions on all religious expression in authorities offices and state-run institutions, including universities, usually for the stated reason of preserving the secular state, and distance of state to all kinds of beliefs. The Constitution establishes the state as a secular country and provides for freedom of conventionalities, freedom of worship, and the individual broadcasting of religious ideas. However, other constitutional provisions regarding the integrity and existence of the secular state restrict these rights. The secularity, bearing a meaning of a protection of believers, plays an of import role to protect the state.

While virtually of the secular countries take religious schools and educational system, one in Turkey can only take religious teachings later a state decided age; which is considered as a necessity given the fact that Turkey is the just considerably secular country in the Muslim world, i.e. it is claimed that weather to establish secularism on are different than those in Christian earth. The establishment of private religious schools and universities (regardless of what religion) is forbidden. Only the state controlled Imam-Hatip loftier school is immune which benefits simply Islamic customs in Turkey. This blazon of high schools teach religious subjects with modernistic positive scientific discipline. Still, graduates of these schools cannot become to the university to seek higher education in another subject area for instance medicine, law, applied science etc.; considering graduates of these schools are intended to be clerics, rather than existence doctors or lawyers. With the rise of fundamentalism in schools, more than 370 Turkish schools take signed a political declaration by the High School Students Matrimony of Turkey (TLB) in order to protestation what they perceive as anti-secularism in schools. Accordingly, at that place has been a ascent in voiced objections to the conversion of schools into an Imam-Hatip, which has affected many Turkish schools since 2012. Many parents have complained near the increasing pressure of schools to become an Imam-Hatip.[twenty]

The Government oversees Muslim religious facilities and education through its Ministry building of Religious Affairs (Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı), which reports directly to the Prime Ministry. The Diyanet has responsibleness for regulating the operation of the state's 75,000 registered mosques and employing local and provincial imams, who are civil servants. Some groups, particularly Alevis, claim that the Diyanet reflects mainstream Islamic behavior to the exclusion of other behavior. The authorities asserts that the Diyanet treats equally all who asking services. However, Alevis do not utilize Mosques or the imams for their worship ceremonies. Alevi ceremonies take place in Cem Houses and led by Dedes who do non benefit from the large budget of the Religious Affairs.

Diyanet and secularism [edit]

Reforms going in the management of secularism have been completed under Atatürk (abolition of the caliphate, etc.).

Notwithstanding, Turkey is non strictly a secular country:

- there is no separation between religion and the country

- there is a tutelage of faith by the state

However, each is free of his religious behavior.

There is an administration called "Presidency of Religious Affairs" or Diyanet[21] manages 77,500 mosques. This country agency, established past Atatürk (1924), finance just Sunni Muslim worship[ citation needed ] Other religions must ensure a financially self-sustaining running and they face up administrative obstacles during operation.[22]

The Diyanet is an official state institution established in 1924 and works to provide Quranic education for children, too every bit drafting weekly sermons delivered to approximately 85,000 different mosques. Furthermore, the Diyanet employs all of the imams in Turkey.[23]

When collecting tax, all Turkish citizens are equal. The taxation rate is non based on religion. However, through the Diyanet, Turkish citizens are not equal in the use of acquirement. The Presidency of Religious Affairs, which has a upkeep over U.S. $two.5 billion in 2012, finance only Sunni Muslim worship.[24]

This situation presents a theological trouble, insofar as Islam stipulates, through the notion of haram (Qur'an, Surah half-dozen, poetry 152), that we must "give total measure and total weight in all justice".

Sufi orders like Alevi-Bektashi, Bayrami-Jelveti, Halveti (Gulshani, Jerrahi, Nasuhi, Rahmani, Sunbuli, Ussaki), Hurufi-Rüfai, Malamati, Mevlevi, Nakşibendi (Halidi, Haqqani), Qadiri-Galibi and Ja'fari Muslims[25] are not officially recognized.

Headscarf result [edit]

| Do you cover when going exterior?[26] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2012 | ||

| No, I do not | 47.3% | 66.5% | |

| Yep, I wear a headscarf | 33.4% | 18.8% | |

| Yeah, I wearable a türban | 15.7% | eleven.4% | |

| Yes, I clothing a çarşaf | 3.4% | 0.i% | |

| NI/NA | 0.three% | two.ii% | |

Although intellectual debates on the function of Islam attracted widespread interest, they did not provoke the kind of controversy that erupted over the issue of appropriate attire for Muslim women. During the early 1980s, female college students who were determined to demonstrate their delivery to Islam began to cover their heads and necks with scarves and wear long, shape-concealing overcoats. The appearance of these women in the citadels of Turkish secularism shocked those men and women who tended to perceive such attire equally a symbol of the Islamic traditionalism they rejected. Militant secularists persuaded the Higher Educational activity Council to issue a regulation in 1987 forbidding female academy students to cover their heads in form. Protests past thousands of religious students and some university professors forced several universities to waive enforcement of the apparel code. The issue continued to exist seriously divisive in the mid-1990s. Throughout the start one-half of the 1990s, highly educated, articulate but religiously pious women take appeared in public dressed in Islamic attire that conceals all merely their faces and easily. Other women, especially in Ankara, Istanbul, and İzmir, take demonstrated against such attire by wearing revealing fashions and Atatürk badges. The effect is discussed and debated in almost every type of forum – artistic, commercial, cultural, economic, political, and religious. For many citizens of Turkey, women'due south dress has get the upshot that defines whether a Muslim is secularist or religious. In 2010, the Turkish Higher Educational council (YÖK) lifted the ban on headscarves at the universities. Since the start of his presidency, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has drastically increased the corporeality of religious high schools across Turkey to back up his programme on bringing up a more pious generation. All the same, this push button on piousness in schoolhouse children seems to have had an adverse effect, for there is anecdotal evidence of a notable amount of Turkish students from religious high schools albeit their loss of faith in Islamic beliefs, which has caused substantial amount of discussion among politicians and religious clerics.[27]

More recently in 2016, Turkey approved hijab as the role of the official constabulary uniform. For the showtime time, female officers volition be able to cover their heads with a headscarf under their police caps. This act was pushed by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan'southward Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) that have been pushing for relaxed restrictions on the hijab.

Denominations [edit]

Many of Islam'due south denominations are practised in Turkey

Sunni Islam [edit]

The vast majority of the present-solar day Turkish people are Muslim and the nearly popular school of constabulary is the Hanafite madh'hab of Sunni Islam according to the KONDA Research and Consultancy survey carried out throughout Turkey in 2007.[28] [ failed verification ] The Hanafi madhhab was the official school of Islamic jurisprudence espoused past the Ottoman Empire[29] [xxx] and a 2013 survey conducted by the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs indicates that 77.v percent of Turkish Muslims place themselves equally Hanafis.[31] Although the Maturidi and Ash'ari schools of Islamic theology (which apply Ilm al-Kalam or rational idea to sympathise the Quran and the hadith) accept been the dominant creeds in Turkey due to their widespread acceptance and propagation since the beginning of the Ottoman Empire,[29] the Athari (literalist) creed[32] of the Salafi movement has seen increasing acceptance.[30]

Compared to the Hanbali schoolhouse of Islam, the Hanafi schoolhouse of Islam takes a much more liberal take on the organized religion, allowing for a more lenient interpretation of religious law.[33]

The Sunni Islamic faith has continuously been a domineering organized religion since 661. The proper name Sunni originates from the emphasis of importance on the Sunna, which is related to the institution of the Shari'a laws.[34]

In Turkey, Muhammad is often called "Hazret-i Muhammed" or "Peygamber Efendimiz" (Our Prophet).[35]

Shia Islam [edit]

Twelver branch of Shia Islam Muslim population of Turkey is composed of Ja'fari aqidah and fiqh, Batiniyya-Sufism aqidah of Maymūn'al-Qāddāhī fiqh of the Alevīs, and Cillī aqidah of Maymūn ibn Abu'l-Qāsim Sulaiman ibn Ahmad ibn at-Tabarānī fiqh of the Alawites,[36] [37] who altogether constitutes nearly one tertiary of the whole population of the country. (An approximate for the Turkish Alevi population varies between Seven and Xi Millions.[7] [38] Over 75% of the population, on the other mitt, overwhelmingly constitute Maturidi aqidah of the Hanafi fiqh and Ash'ari aqidah of the Shafi'i fiqh of the Sunni followers.)

Dissimilar the common usage of the term "Shi'a" in other languages, Aleviler instead is being frequently used to stand for all the Shi'a Muslim sects in Turkish language. Furthermore, the term Kızılbaş in the history was used pejoratively for all Shi'ites in Anatolia.

Alevis [edit]

In that location are an estimated seven-9 meg Alevi in Turkey which approximately constitutes ten% of the total population.[1] [39]

- The Alevi ʿaqīdah

- Some of their members (or sub-groups, particularly those belonging to Qizilbash and Hurufism) claim that God takes dwelling in the bodies of the human-beings (ḥulūl), believe in metempsychosis (tanāsukh),[40]

- Some of the Alevis criticize the course of Islam as it is being adept overwhelmingly past more than 99% of Sunni and Shia population.[41]

- Regular daily salat and fasting in the holy month of Ramadan are not officially done by the Qizilbashs, Hurufis, and Ishikist groups. These members of Yazdânism like Ishikists and Yarsanis who portrayed themselves as Alevis, are oftentimes denounced by the Dedes.

Ja'faris [edit]

The followers of the Ja'fari jurisprudence constitute the third sizable community with their more than iii million members and about of them lives in the eastern provinces neighboring to Azerbaijan, more particularly in the Iğdır Province. They have lxx mosques in Istanbul and some 300 throughout the country and receive no state funding for their mosques and imams as the Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) is exclusively Sunni.[42]

Alawites [edit]

The majority of the Alawite customs in Turkey with an estimated population of effectually 1,000,000[43] lives in the Province of Hatay, where they nearly stand for half of the full population,[44] primarily in the districts of Arsuz,[45] Defne and Samandağ,[43] where Alawites institute the majority and in Iskenderun and Antakya where they constitute a significant minority of the population. Larger Alawite communities can as well be found in the Çukurova region, mostly in and effectually the cities of Adana, Tarsus and Mersin.[16]

Sufism [edit]

Folk Islam in Turkey has derived many of its popular practices from Sufism which has good presence in Turkey and Egypt. Particular Sufi shaikhs – and occasionally other individuals reputed to be pious – were regarded later on decease as saints having special powers. Veneration of saints (both male person and female) and pilgrimages to their shrines and graves represent an important aspect of popular Islam in the country. Folk Islam has continued to cover such practices although the veneration of saints officially has been discouraged since the 1930s. Plaques posted in various sanctuaries forbid the lighting of candles, the offering of votive objects, and related devotional activities in these places. Modern twenty-four hours Sufi shaykhs with large adherents in Turkey include Shaykh Mehmet Efendi[ who? ] (residing in Istanbul) and Mawlana Sheikh Nazim Al-Haqqani who resided in Lefka, North Republic of cyprus, until his death in May, 2014.

Quranism [edit]

Those who do non accept the authority of hadith, known as Quranists, Quraniyoon, or Ahl al-Quran, are also present in Turkey.[46] [47] In Turkey, Quranist ideas became particularly noticeable, with portions of the youth either leaving Islam or converting to Quranism.[48] There has been significant Quranist scholarship in Turkey, with there being even Quranist theology professors in significant universities, including scholars similar Yaşar Nuri Öztürk[49] and Caner Taslaman.[50] Some believe that there are secret Quranists even in the Diyanet itself.

The Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) regularly criticizes and insults Quranists, gives them no recognition and calls them kafirs (disbelievers).[51] Quranists responded with arguments and challenged them to a debate.[52]

| Religions | Estimated population | Expropriation measures[53] | Official recognition through the Constitution or international treaties | Government Financing of places of worship and religious staff |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunni Islam - Hanafi & Shafi'i | 78.ii to 84.7% (60 to 64 million) | No | Yes through the Diyanet mentioned in the Constitution (art.136)[54] | Yep through the Diyanet[55] |

| Shia Islam - Alevi[56] | nine to 14.5% (7 to 11 million) | Yes[25] | No.[57] In the early fifteenth century,[58] due to the unsustainable Ottoman oppression, Alevis supported Shah Ismail I who had Turkmen origins. Shah Ismail I supporters, who article of clothing a carmine cap with twelvefolds in reference to the 12 Imams were called Qizilbash. Ottomans considered the Qizilbash (Alevi) as enemies considering of their Turkmen origins.[58] [ unreliable source? ] Today, Cemevi, places of worship of Alevi-Bektashi have no official recognition. | No[55] |

| Shia Islam - Bektashi[56] | No.[57] In 1826 with the abolition of the Janissary corps, the Bektashi tekke (dervish convent) were closed.[25] [59] | |||

| Shia Islam - Ja'fari | iv% (three million)[60] | No[57] | No[55] | |

| Shia Islam - Nusayrīya[56] | around 1 1000000[43] | No[57] | No[55] | |

| Ghair Muqallid and Quranist Muslim | ii% (1.v million)[x] | - | - | - |

Turkey's role in the Islamic Globe [edit]

Turkey is a founding fellow member of the Arrangement of Islamic Cooperation (OIC, formerly the Organisation of the Islamic Conference). The headquarters of some Islamic organizations are located in Turkey:

- The Islamic Briefing Youth Forum for Dialogue and Cooperation (ICYF-DC) in Istanbul

- The Research Center for Islamic History, Art and Civilisation (IRCICA), in Istanbul, and

- The Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Center for Islamic Countries (SESRIC) in Ankara.

See also [edit]

- Organized religion in Turkey

- Secularism in Turkey

- Minorities in Turkey

- Islam by country

Notes [edit]

- ^ While it is incommunicable to know the exact pct, this is the minimum guess via poll results[ citation needed ]

- ^ Withal, these are based on the existing religion data written on every citizen'southward national id menu, that is automatically passed on from the parents to every newborn, and exercise not necessarily represent individual choice. Furthermore, anyone who was non officially registered as Christian or Jewish past the time of the foundation of the republic, was automatically recorded as Muslim, and this characterization has been passed down to new generations. Therefore, the official number of Muslims besides include people with no religion; converted from Islam to a different organized religion than Islam; and anyone who is of a different religion than their parents, but hasn't applied for a modify of their private records.

References [edit]

- ^ a b c "Turkey: International Religious Liberty Report 2007". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "İşte Türkiye'nin dini hayat haritası". aksam.com.tr (in Turkish). Archived from the original on five June 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "Türkiye'de Dini Hayat Araştırması". www.aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 27 February 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "Türkiye nüfusunun yüzde 99,2'si Müslüman". www.trthaber.com (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "Religious Composition past Country, 2010-2050". Pew Research Center. 12 April 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Aktas, Vahap (1 Jan 2014). "Islamization of Anatolia and the Effects of Established Sufism (Orders)". The Anthropologist. 17 (1): 147–155. doi:10.1080/09720073.2014.11891424. ISSN 0972-0073. S2CID 55540974. Archived from the original on 22 Nov 2021. Retrieved 27 Oct 2020.

- ^ a b "Religions". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "TURKEY" (PDF). Library of Congress: Federal Research Division. Archived from the original on 25 Dec 2018. Retrieved 1 Nov 2010.

- ^ "State – Turkey". Joshua Project. Archived from the original on xx March 2016. Retrieved 27 Apr 2014.

- ^ a b c "Pew Forum on Religious & Public life". pewforum.org. ix Baronial 2012. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ "Sufism". All about Turkey. xx November 2006. Archived from the original on eight June 2008. Retrieved i November 2010.

- ^ ÖZKÖK, Ertuğrul. "Türkiye artık yüzde 99'u müslüman olan ülke değil". www.hurriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved xiii August 2020.

- ^ "Optimar'dan din-inanç anketi: Yüzde 89 Allah'ın varlığına ve birliğine inanıyor". T24.com.tr. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved iv Apr 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ "Syria strife tests Turkish Alawites | Turkey | al Jazeera". Archived from the original on 1 Oct 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b Prochazka-Eisl, Gisela. "The Arabic speaking Alawis of the Çukurova: The transformation of a linguistic into a purely religious minority". Christiane Bulut: Linguistic Minorities in Turkey and Turkic-Speaking Minorities of the Peripheries, Harrassowitz (Wiesbaden) Forthcoming. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Gregorian, Vartan. Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith, Brookings Establishment Printing, 2003, pp. 26–38 ISBN 0-8157-3283-X

- ^ Strickland, Ballad (3 August 2009). "Mosque mod". Christian Scientific discipline Monitor. Archived from the original on 19 Nov 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Öztürk, Ahmet Erdi (26 February 2019). "An alternative reading of faith and absolutism: the new logic between organized religion and state in the AKP'due south New Turkey" (PDF). Southeast European and Blackness Sea Studies. nineteen: 79–98. doi:10.1080/14683857.2019.1576370. ISSN 1468-3857. S2CID 159047564. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Girit, Selin (21 June 2016). "Turkish students fear assault on secular education". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 10 Nov 2019.

- ^ "T.C. Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı | İman | İbadet | Namaz | Ahlak". Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Ahmet Erdi Öztürk (2016). "Turkey's Diyanet nether AKP rule: from protector to imposer of state ideology?" (PDF). Southeast European and Black Body of water Studies. 16 (4): 619–635. doi:x.1080/14683857.2016.1233663. S2CID 151448076. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ "CSIA". Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved xi November 2019.

- ^ Sözeri, Semiha; Öztürk, Ahmet Erdi (September 2018). "Diyanet equally a Turkish Foreign Policy Tool: Evidence from the Netherlands and Republic of bulgaria" (PDF). Politics and Organized religion. eleven (3): 624–648. doi:10.1017/S175504831700075X. ISSN 1755-0483. S2CID 148657630. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ a b c The World of the Alevis: Issues of Culture and Identity, Gloria 50. Clarke

- ^ Fromm, Ali Çarkoğlu, Binnaz Toprak; translated from Turkish past Çiğdem Aksoy (2007). Religion, Society and Politics in a Changing Turkey (PDF). Karaköy, İstanbul: TESEV publications. p. 64. ISBN978-975-8112-xc-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Girit, Selin (10 May 2018). "Losing their religion: The young Turks rejecting Islam". Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved x Nov 2019.

- ^ KONDA Enquiry and Consultancy (viii September 2007). "Organized religion, Secularism and the Veil in daily life" (PDF). Milliyet. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009.

- ^ a b McLean, George F. (1996). Normative Ethics and Objective Reason. CRVP. ISBN978-one-56518-022-ii. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved twenty August 2015.

- ^ a b "Salafism Infiltrates Turkish Religious Discourse". Middle Due east Establish. Archived from the original on xi September 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Aydoğan Vatandaş, "Tin Turkey exist ISIL'due south next phase", Today's Zaman Archived 2015-10-25 at the Wayback Machine Oct 16, 2015

- ^ Halverson, Theology and Creed in Sunni Islam, 2010: 38–48

- ^ Tol, Gonul (10 January 2019). "Turkey's Bid for Religious Leadership". Foreign Affairs : America and the Earth. ISSN 0015-7120. Archived from the original on ten November 2019. Retrieved 10 Nov 2019.

- ^ "Muslim sects - All About Turkey". All Well-nigh Turkey. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (1990). Islamic Names: An Introduction (Islamic Surveys) . Edinburgh Academy Press. p. 30. ISBN978-0-85224-563-seven.

- ^ "Muhammad ibn Āliyy'ūl Cillī aqidah" of "Maymūn ibn Abu'fifty-Qāsim Sulaiman ibn Ahmad ibn at-Tabarānī fiqh" (Sūlaiman Affandy, Al-Bākūrat'ūs Sūlaiman'īyyah - Family unit tree of the Nusayri Tariqat, pp. fourteen–15, Beirut, 1873.)

- ^ Both Muhammad ibn Āliyy'ūl Cillī and Maymūn ibn Abu'l-Qāsim'at-Tabarānī were the murids of "Al-Khaṣībī", the founder of the Nusayri tariqa.

- ^ "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved ix July 2016.

- ^ "Turkey's Alevi strive for recognition". Asia Times Online. 18 February 2010. Archived from the original on 22 February 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Halm, Heinz (21 July 2004). Shi'ism. Edinburgh University Press. p. 154. ISBN978-0-7486-1888-0.

- ^ Yaşar Nuri Öztürk, Kur'an'daki İslam.

- ^ "Turkish Shiites fear growing hate crimes - Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East". world wide web.al-monitor.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Cassel, Matthew. "Syria strife tests Turkish Alawites". Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 23 Feb 2017.

- ^ Sotloff, Steven (10 September 2012). "The Alawite Towns That Support Syria'southward Assad — in Turkey". Fourth dimension. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2017 – via earth.time.com.

- ^ simitincilicia (thirty September 2012). "A Weekend in Arsuz". Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Aisha Y. Musa, The Qur'anists Archived 2013-07-19 at the Wayback Machine, nineteen.org, Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Turkish News - Latest News from Turkey". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Öztürk: Modern Döneme Özgü Bir Kur'an Tasavvuru. 2010, S. 24.

- ^ Mustafa Akyol, Islam without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty, West.W. Norton & Company, 2011, p. 234

- ^ "Associates and Affiliates". 19.org. Archived from the original on 12 July 2013. Retrieved xiv July 2013.

- ^ Patheos.com: „Quran, Hadiths or Both? Where Quranists and Traditional Islam Differ." [21.1.2020].

- ^ altmuslim (19 Apr 2018). "Quran, Hadiths or Both? Where Quranists and Traditional Islam Differ". altmuslim. Archived from the original on 10 Baronial 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "Le gouvernement turc va restituer des biens saisis à des minorités religieuses". La Croix. 29 August 2011. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 23 Feb 2017 – via www.la-croix.com.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on eight December 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ a b c d "Cahiers de L'obtic" (PDF). Observatoire de recherche interdisciplinaire sur la Turquie contemporaine. Dec 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Not recognized every bit an Islamic fiqh madh'hab past the Amman Message.

- ^ a b c d "Les minorités non musulmanes en Turquie : "certains rapports d'ONG parlent d'une logique d'attrition", find Jean-Paul Burdy". Archived from the original on 28 November 2017. Retrieved 23 Feb 2017.

- ^ a b Bacqué-Grammont, Jean-Louis (1979). "Notes et documents sur les Ottomans, les Safavides et la Géorgie, 1516-1521". Cahiers du Monde Russe et Soviétique. 20 (ii): 239–272. doi:10.3406/cmr.1979.1359.

- ^ "Blog Hautetfort : Erreur 404". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Rapport Minority Rights Group Bir eşitlik arayışı: Türkiye'de azınlıklar Uluslararası Azınlık Hakları Grubu 2007 Dilek Kurban

Further reading [edit]

- Bein, Amit. Ottoman Ulema, Turkish Republic: Agents of Change and Guardians of Tradition (2011) Amazon.com

- Karakas, Cemal (2007) "Turkey. Islam and Laicism Between the Interests of State, Politics and Guild". Peace Inquiry Institute Frankfurt (PRIF), Germany, PRIF-Report No. 78/2007.

- Smith, Thomas West. (2005) "Betwixt Allah and Ataturk: Liberal Islam in Turkey", The International Journal of Human Rights, Vol. 9, No. 3., pp. 307–325.

- Yavuz, Thou. Hakan. Islamic Political Identity in Turkey (2003) Amazon.com

- Chopra, R.M., Sufism, 2016, Anuradha Prakashan, New Delhi. ISBN 978-93-85083-52-5.

- Yavuz, Chiliad. Hakan and Öztürk, Ahmet Erdi (2019), "Turkish Secularism and Islam Under the Reign of Erdoğan", Southeast and Black Bounding main Studies, Vol. 19, NO. ane; https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2019.1580828

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islam_in_Turkey

0 Response to "When Has Islam Become Present in Turkey Again Economic Clip Art"

Post a Comment